The director of the Paris Opéra, Emile Perrin, was guided by a happy intuition when in 1865 he sent the 52-year-old Verdi a scenario for an opera based on Schiller’s “dramatic poem” Don Karlos, Infant von Spanien (Don Carlos, Infante of Spain), hoping to move the composer to write a new work for him. Schiller being one of Verdi’s favourite dramatists along with Shakespeare and Victor Hugo, he was soon filled with enthusiasm for the project. He took a close interest in the writing of the French libretto, keen to explore the literary model in all its complexity in adapting it for the operatic stage, in contrast to the approach he had taken with his early Schiller operas – Giovanna d’Arco, I masnadieri and Luisa Miller. Premiered in Paris on 11 March 1867, Don Carlos was to be the longest and most ambitious of all his operas. Taking as its basis Schiller’s drama of ideas, which adheres only loosely to historical circumstance, the opera became a work that interweaves the political and the personal in a more complex fashion than any other in Verdi’s œuvre.

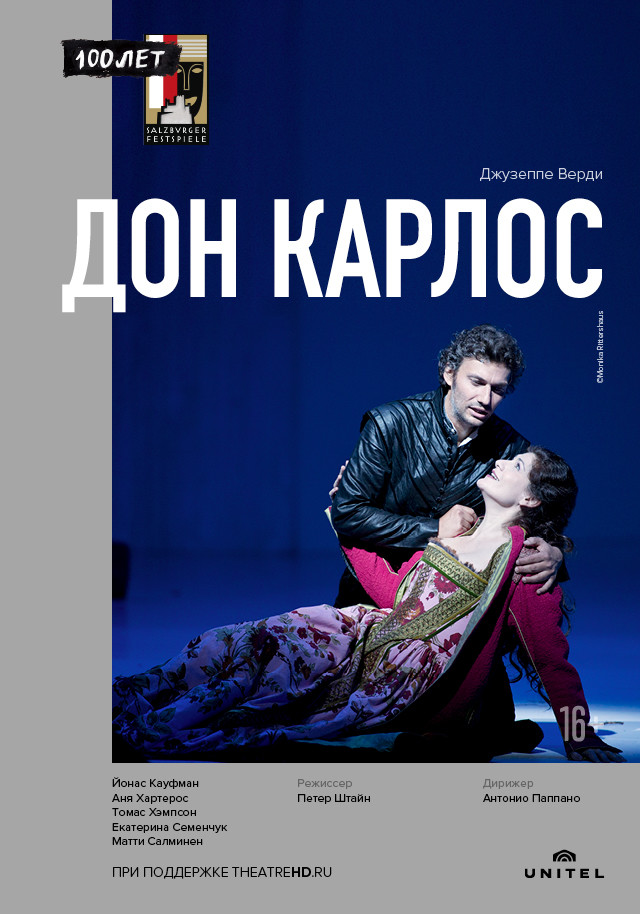

Verdi defended the length of his Don Carlos in 1871, saying “It is true that it is a long opera. But that is how it must be”. Nonetheless, the constraints of the theatre of that time led him to thoroughly revise and condense the opera a decade later. He cut the first act set in Fontainebleau together with other passages and made numerous, in some instances radical changes. This four-act version, which was staged in Italian at La Scala in Milan in 1884, then had the original first act restored for a subsequent performance in Modena in 1886. For the 2013 Salzburg Festival Peter Stein and Antonio Pappano are working on the original version of the opera – albeit in Italian and minus the ballet. However, it will include those passages that were cut shortly before the first performance in 1867, for example the prelude to Act One with the chorus of woodcutters and their families, which highlights the dire plight of the French people resulting from the winter and the war with Spain.

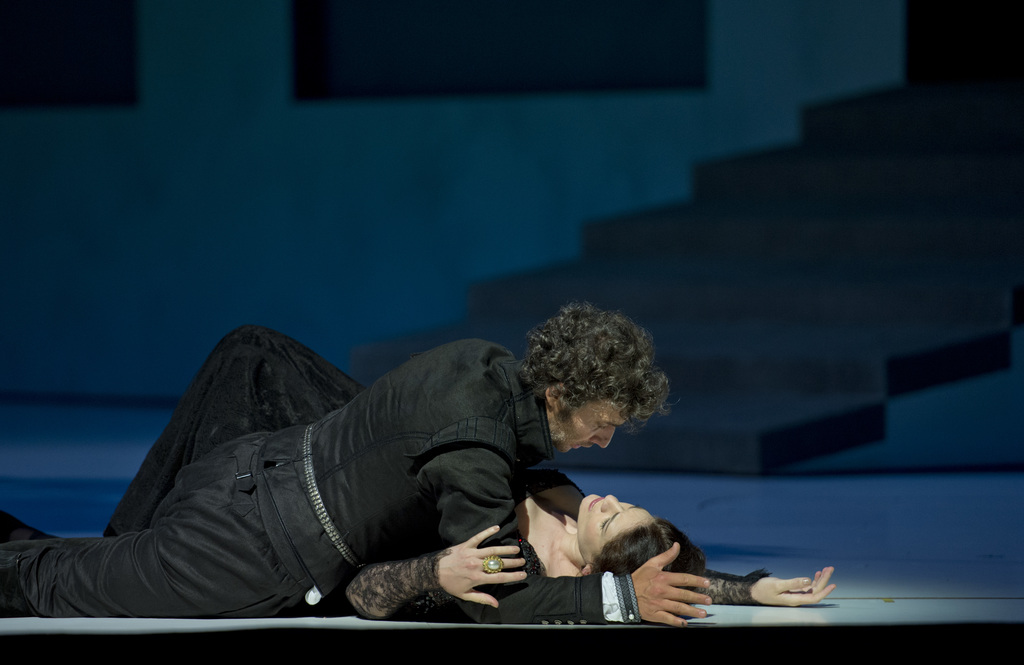

It is only when the Fontainebleau act is retained that the premises for the subsequent development of the plot become evident, making the psychological development of Elisabetta di Valois and Don Carlo (as the protagonists are called in the Italian version) far more convincing. In the forest of Fontainebleau, where the daughter of the French king encounters the Spanish infante to whom she has been promised, the couple experience their only moment of happiness. With the cannon fire that heralds the conclusion of the peace between Spain and France harsh reality obtrudes: a page announces that Elisabetta is not to marry Carlo but the Spanish king Filippo. For reasons of state she agrees – and Carlo’s bride thus suddenly becomes his mother, a traumatic blow that leaves both of them with lasting emotional damage. In the two later duets between Carlo and Elisabetta Verdi explores the subtlest psychological ramifications, portraying the path of an impossible love whose ultimate end is a flight into the metaphysical: “Embracing one another we will find in God that happiness which constantly eludes us on earth!”

The king is also filled with a longing for death. As an exponent of a ruthlessly authoritarian system who perceives the world around him as hostile and confronts it with distrust, Filippo has lost all connection to his fellow human beings and is emotionally impoverished. Seldom has Verdi given such a harrowing representation of the loneliness of the powerful – a subject that had always interested him – as in Filippo’s great scene in Act Four. It is the desolate reverse of the absolute power that the king represents in the auto-da-fé immediately preceding this scene. Verdi had requested a crowd scene from his librettists from the outset, wanting to vie with the grand opéras of Meyerbeer, who had united spectacle and drame with such consummate mastery and had died only a short time previously in 1864.

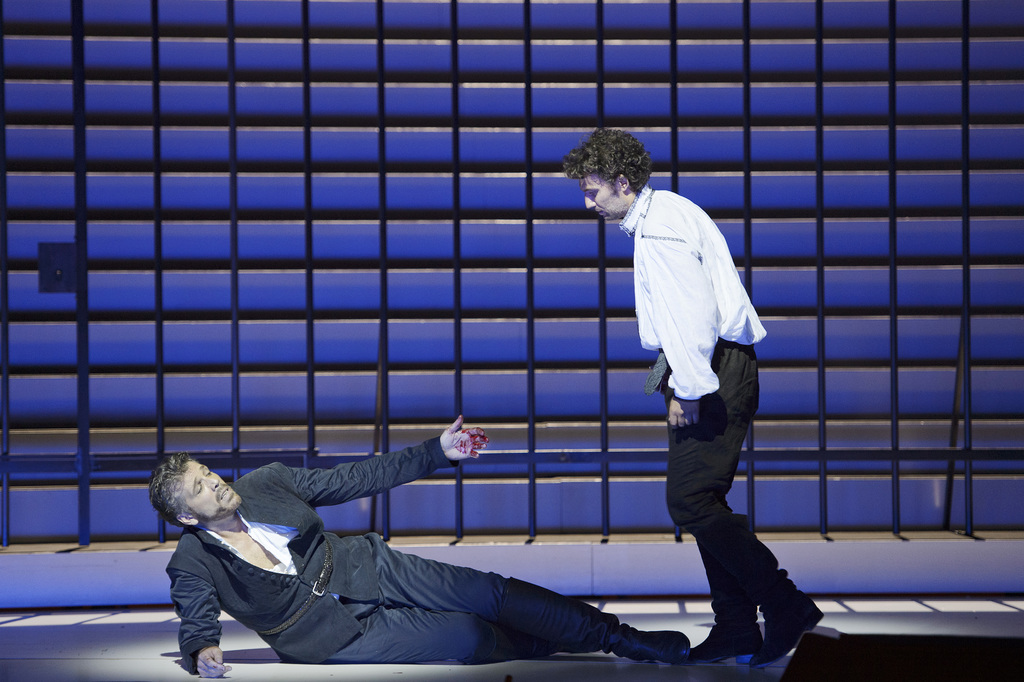

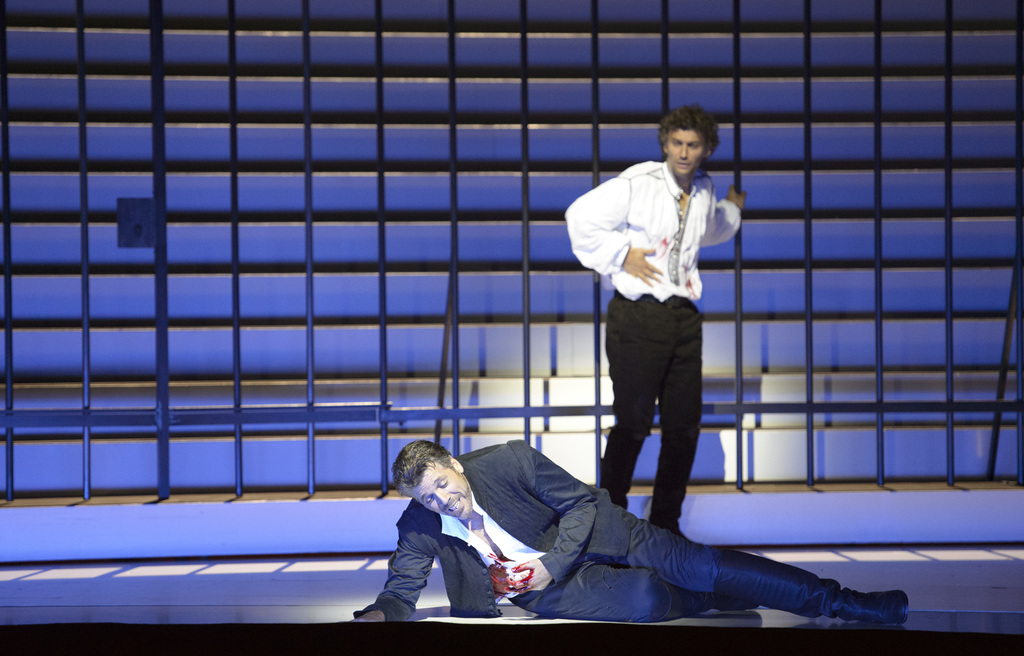

If Filippo embodies a political order oriented towards the preservation of power and unquestioning obedience, the Marquis of Posa seems like a mouthpiece of liberal ideas and humanitarian values that has slipped into the plot from a later age. Paradoxically, Filippo only comes to trust the Marquis because the latter encounters him with courageous frankness, even daring to contradict him. Posa’s actual adversary is thus not the king but the Grand Inquisitor. A lifelong anticlericalist, Verdi portrays him as a dehumanized, unscrupulous politician who dresses up his decisions in ideological guise, presenting them as objective truth. The only way in which the Grand Inquisitor can counter the “spirit of innovation” that speaks from Posa’s mouth and imperils the Church’s fundament of power is with the utmost severity. The king proves himself to be his helpless puppet: although Posa is the only person to whom he can entrust his deepest cares, irrespective of their political differences, Filippo has him killed. Verdi captures his pain at the loss of his “friend” in a haunting melody that he was later to revisit in the Lacrimosa of his Requiem: “Who will restore this dead man to me?”

In no other opera did Verdi explore such a rich variety of human relationships as in Don Carlo. His music invokes no less powerfully the scenes of the action and the atmosphere of hopelessness that dominates this dark drama from the very beginning.